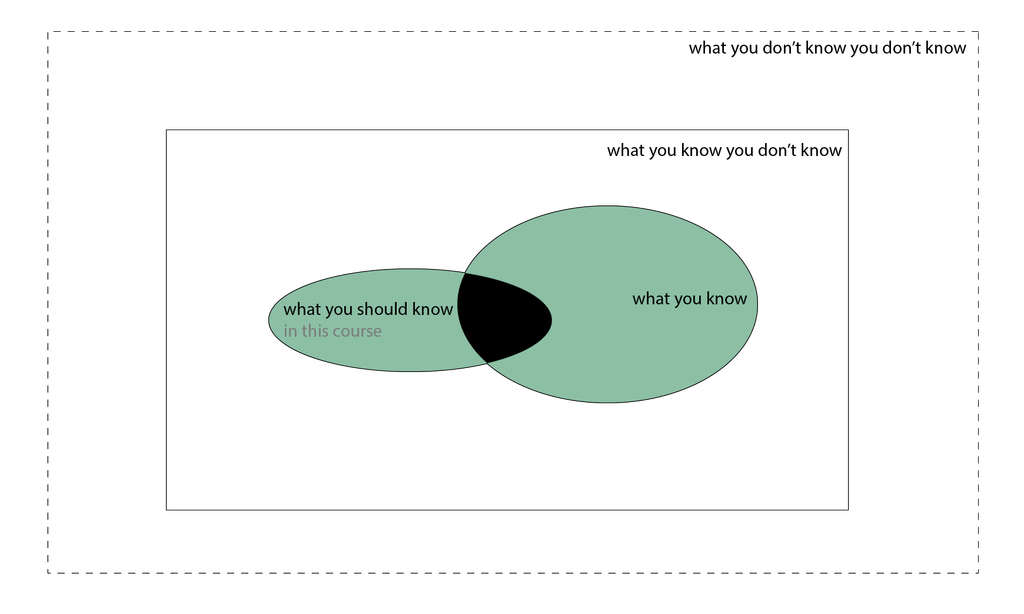

I wrote in the previous post that you don’t know what you don’t know, and that can be harmful. This post aims to show a systematic way to increase the set of things that we know are not your knowledge (a.k.a. the known unknowns).

But firstly, just why do we need to increase our known unknowns (the number of things that we know we don’t know)?

Why you should know what you don’t know

You will be more open to learning new things

Individuals who are ignorant of their ignorance are not motivated to learn more. If you are not aware of the scarcity of your knowledge, confidence can surround you like a bubble. It clouds your vision to the vastness of the knowledge around you. Have you ever talked to a proud person who is born much earlier than you and believes that they have seen it all? It is difficult to convince them that they are not the ultimate truth in the universe, precisely because they don’t know how much they don’t know. This is a vicious cycle – the less you know, the likelier you stay uninformed. On the contrary, the more you know you don’t know, you are more eager for and open to learning new things, and therefore know more.

Less confirmation bias, more security in what you do know

Remember the confidence bubble? It can burst. Suppose you spent a good 4 years studying fluid dynamics with the assumption that gravity is constant, but one day realise that: that thing changes. I hope you are still well. Confirmation bias is a psychology term stemming from the idea that people tend to hang on to their favoured hypotheses with unwarranted tenacity and confidence (Klayman, 1995, p.385). When presented with a cluster of evidence and facts, we generally only pick up what aligns with our beliefs. It is a key weakness of human consciousness and hinders us from getting to sound truth. It is hard to eliminate confirmation bias, but in increasing our known unknowns (when we are at least aware of what we don’t know), we make a conscious effort towards fighting it.

It is an easy-to-obtain knowledge

Knowing that you don’t know something is a knowledge in itself. You know that you don’t know about dolphins’ biological construct, and that’s a knowledge! And it’s so easy to obtain! An additional knowledge can come with hundreds of known unknown. See proof below.

How to know what you don’t know

We begin with some definitions.

Knowns, K: Things that you know

Unknowns, U: Things that you don’t known

Known Unknowns, KU: Things that you know that you don’t know

Unknown Unknowns, UU: Things that you don’t know that you don’t know

| you know | you don’t know |

|---|---|

| K | U |

| KU | UU |

K, U, KU, UU knowledge table

Now, the meat.

[1] The first step is to consider this formula:

which is

coming from that

(i.e. what you know is the ratio of your knowledge and 1, the set of all things true, normalized.)

Assuming that knowledge for any given truth is a binary state, implying that you can only know or don’t know something, but not both at the same time.

[2] And examine what you know.

You look at what you know, and examine the implications.

Suppose I know one more thing today: the price of a panini at the cafe across the road (it is almost 2pm now and I have eaten only cereal.) It gives me great pride to know one more thing. However, this knowledge is a statement that implies a lot of things:

Price of panini at Cafe X across the street = $6.9

=> Cafe X sells paninis

=> a panini has a price

=> Cafe X is a cafe in Edmonton

Implications of a panini statement

[3] proceed to consider the flip side of what you know.

| what I don’t know | = 1 – (a panini’s price) |

| = all other meal prices in the cafe + æ |

where æ is all other elements not related in the present case, i.e. a bunch of other things. And so if I set out to find the prices of other meals in the cafe, I become aware of more unknowns:

| what I don’t know | = 1 – (all prices at this cafe) |

| = all meal prices in other cafes in the world + æ |

Quite an escalation. By knowing the price of a panini at a cafe, I now know that I don’t know a lot of things:

| I know that | This means that I don’t know that |

|---|---|

| Cafe X sells paninis | 1 - Cafe X sells paninis = all other things sold at Cafe X + æ |

| A panini has a price | 1 - price of paninis = price of all other things + æ |

| Cafe X is a cafe in Edmonton | 1 - Cafe X is in Edmonton = all other cafes + æ |

| … | … |

| prices of everything in all other cafes |

example of the flip sides of panini statement.

I find this exercise quite fun. Examine your existing knowledge (that you are interested in) and go through this process. That’s how you can guide yourself to knowing what you don’t know.

What do you think? Please let me know one of the many things missed out here.

Appendix:

Proof – An Increase in K will always result in an increase in KU

The marginal increase of KU is always positive given an increment of KK. This holds true for all instances of knowledge (statement) with at least one implication.

Let µ = a piece of knowledge Let Ω = set of all knowledge

= infinity, ∞

= 1

= K + KU + U + UU

Proof. For gain of µ to result in no net increase in KU, µ must be either a knowledge (statement) with no attributes (implications), or a knowledge of which attributes are already completely and exhaustively known (which must be Ω), or µ must be Ω.

We know that no humans holds a knowledge that is Ω.

Therefore, gaining any knowledge with at least one implication will always increase the set of known unknowns. The more you know, the more you know you don’t know.

Reference

- Klayman, Joshua. “Varieties of confirmation bias.” Psychology of learning and motivation 32 (1995): 385-418.

- Feature image is from jeffreyw @ Flickr . Used under license CC BY 2.0

Written by Natasha. Last edited:2018-09-25 00:00:00