We all make choices, but in the end, our choices make us. – Andrew Ryan in Bioshock

Are our choices, seemingly made by ourselves, in fact a mere juncture in a predetermined world? As we face and see the manifestations of our decisions daily, it can be hard to grasp that our choices could have been dictated elsewhere. Philosophical texts proclaim this well, but statistical and economics concept can help us to better understand this.

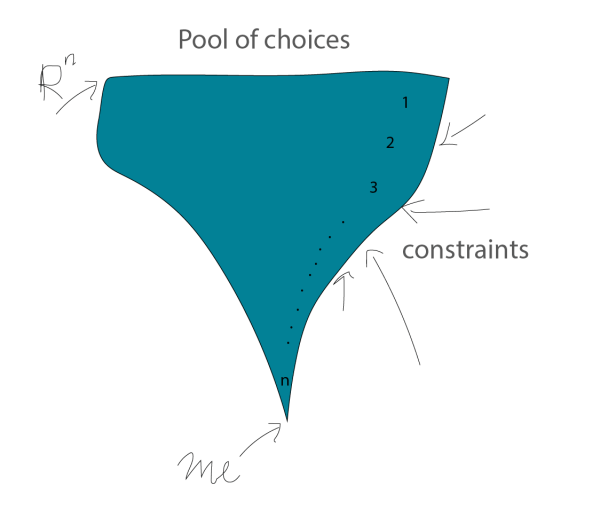

How? Let’s start with the intuition that my sitting here typing on a computer is a causal effect of my thoughts, that I alone chose, with or without constraint. It is a manifestation of my agency. However, think about my circumstance. It is clear that the choices that are open to me are eliminated by constraints at each stage:

The first stage spans the entire space of possible choices that I like to think of as Rn, which includes floating in vacuum near Venus this morning as I sip my tea. Then in stage 2 I realize that I cannot simultaneously exist in a morning and at night to have dinner with morning drinks, thus the pool of choices contracts. Further along the tunnel, probabilities of some events become so negligible as for the events to be dropped from my range of morning activities: e.g. I type because I don’t write on papyrus paper, and that I can hardly imagine doing my typing on a yacht in the Mediterranean. In this way, it is not hard to see how a large proportion of our choices is limited or pre-determined by prevailing events and setup.

However, a lot is to be argued as I arrive at the bottleneck, hypothetically denoted as stage n here: that is, when I can realistically and easily choose between going out for a jog, having tea or coffee, where to sit, and whether or not to write at all, etc. These choices are not unconstrained: if I had hurt my spine the day prior, for example, I would not choose to sit. But it does allow a fairly open field for these remaining choices to be considered equally. If I could take advantage of this plurality of choices, does this mean that my decision is my own?

If I could, then freedom and determinism can coexist: known in philosophy as compatibility.

If I couldn’t, then freedom an determinism cannot coexist: incompatibility.

This is where the debate stalemate gets worse, heated by not only philosophers but also mathematicians and clergy. As famously put forward by Laplace, an 18th century mathematician, statistician, and physicist:

We ought to regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its antecedent state and as the cause of the state that is to follow. An intelligence knowing all the forces acting in nature at a given instant, as well as the momentary positions of all things in the universe, would be able to comprehend in one single formula the motions of the largest bodies as well as the lightest atoms in the world, provided that its intellect were sufficiently powerful to subject all data to analysis; to it nothing would be uncertain, the future as well as the past would be present to its eyes. The perfection that the human mind has been able to give to astronomy affords but a feeble outline of such an intelligence. (Laplace 1820)

In this statement, Laplace in effect declares that predictability and determinism commingle (apart from claiming that there is a higher power that is really good at data analysis.) It is not known to many that Laplace had a primary role in developing Bayes’s law, which is a fundamental formula in every high school probability textbook. The formula, an astoundingly simple way to calculate probabilities of different events, goes:

\[P(A \mid B)= {\frac {P(B\mid A)\,P(A)}{P(B)}}\]where A and B are events and {P(B)\neq 0}.

…and goes on to imply that every event has a predetermined probability.

The disturbing implication from hard determinism rises immediately to the mind. Firstly, individuals can excuse themselves from moral responsibility e.g. I am only doing this because fate dictates so. Secondly, individuals lose initiative: if I can reach what I am destined for notwithstanding what I do, there is little point having any initiatives from now to the day that I die. That is, I will if I have to, but I will not think what could change the status quo and design a roadmap to achieve it. It will happen if it should – why tire myself?

The significance of Laplace’s concept is profound, for we can finally establish mathematically that something can be changed. Within the predetermined world, there is a spectrum of fluid probabilities: if you worked towards a goal, you raise the probability of achieving that goal.

Notes:

- this post is about determinism understood through statistical and economic concepts, and not about economic determinism.

- there are many loopholes in my claims. Please feel free to leave a comment to pinpoint them.

Reference

- Hoefer, Carl, “Causal Determinism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2016/entries/determinism-causal/.

- Laplace, P., 1820, Essai Philosophique sur les Probabilités forming the introduction to his Théorie Analytique des Probabilités, Paris: V Courcier; repr. F.W. Truscott and F.L. Emory (trans.), A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities, New York: Dover, 1951 .

Written by Natasha. Last edited:2018-06-19 09:12:34