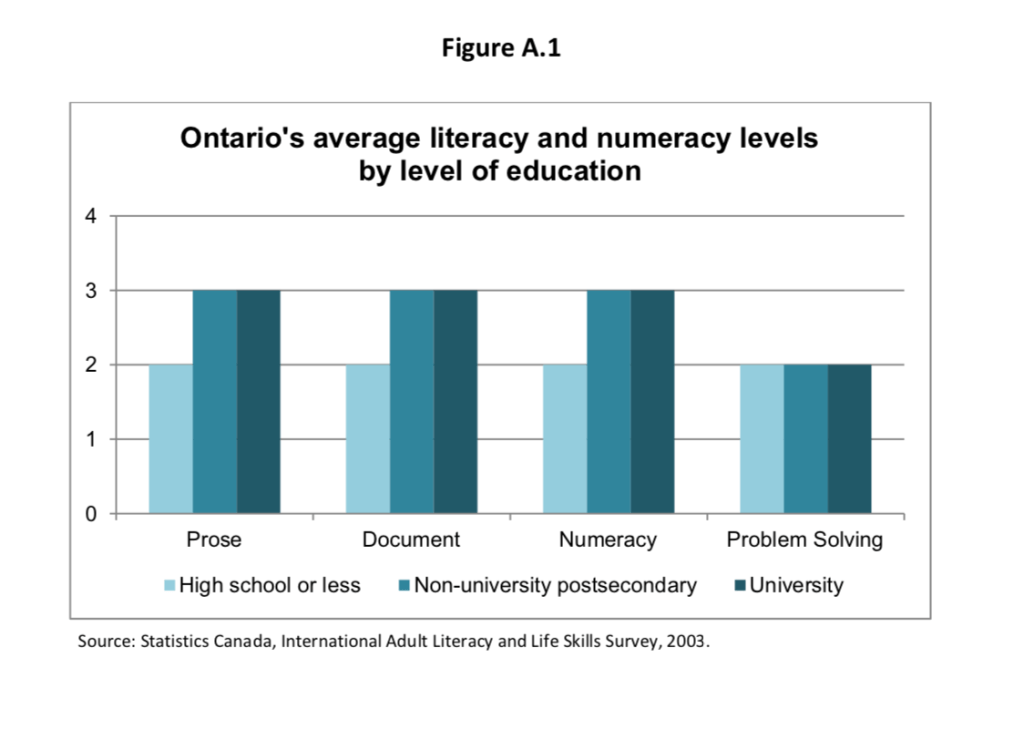

Here is a striking figure:

(Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario HEQCO, 2013)

(Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario HEQCO, 2013)

Figure shows that higher education (in Ontario, conforming to the scope of the report) does not help graduates develop problem solving skills. It also shows that university delivers nothing more in terms of prose, document, and numeracy skills compared to other postsecondary learning institutions e.g. vocational colleges, community colleges, etc.

How am I not surprised?

Yes, I am learning in university. But I do so in a system that decentivises learning. The truth is, I don’t know what exactly the system wants us to learn.

What do you want us to learn?

The skills required in the workplace?

I don’t think so.

But that is OK. In my view, there is little point in going to university to gather hard skills. Skills required in the workplace are diverse and dynamic: leadership, cross-cultural communication, adaptation, packages, languages and new conventions that pop up daily. At any given day, you may have to use multiple concurrent frameworks in constructing a deliverable only to find that it is not compatible with, say, a user terminal. So you have to learn and adapt to a new one with speed: not in 4 years or 8 months–but sometimes the next day. At the same time, university courses have to undergo various developments and gates of approval before they can begin delivering. There is no way university courses can keep up with the changing demands of the world. Therefore, the payoff from using months or years learning a particular hard skill in university is negligible.

I think, if you already have a certain level of employability (if your goal is to get a job), one way to gain value in university is to always take “useless” courses. Intellectual history, political science, mathematical analysis, ancient economic thoughts, fine arts, musical appreciation……the more abstract and theoretical, the better. I think they provide the grounding connecting to any hard skills.

For example, the introductory econometrics course at my university uses a proprietary statistical package called STATA. It has minimal integration ability, a rigid environment, a price tag of $2k apiece, and support from a very small user community. Criticism abound, for graduates can hardly encounter the software outside of the ivory tower. In light of this, a popular opinion is to teach R or SAS instead.

I in fact think this is apt for two reasons. Firstly, R is a popular thing, and students will eventually have to pick up the framework. But without the course, they will not learn STATA. In this way, they gain a novel knowledge. Secondly, because STATA requires no coding but only typing commands, we could go very fast. I remember the pain of learning to importing data and producing my first graphs in matplotlib–but in STATA we did that in 5 minutes, and went on to treatment of topics in inferential statistics in no time. These theoretical learnings are fundamental in application of any cutting-edge technology. Why? After R, there can be R#, or R++, or S, or T, or U, or V. But the application of inferential statistic is what provides the grounding.

The skills required in the world?

No. It does the opposite.

In a world full of temptations, distractions, misleading facts, injustice, and ignorance, universities should do their part in upholding principles. They should educate caring, curious, and intelligent leaders and citizens.

Sadly, it is failing us. I give you several examples from my past academic year to elucidate how the system failed–how we failed. I remind you that this may be observed in many other institutions than my own. Also, this is from the lens of a normal student like me. If you are good at what you do and do not have to waddle, more power to you.

#I think we are failing in 3 key areas:

Kindness and empathy.

In a race to rising above average for a competitive GPA, we fail to empathize.

- I took a night class for spring. There is an alternative session offered in the morning with the same instructor and content.

One might naturally think that some students opt for the night session because it can work with their work schedule.

But once I went on a course discussion group and saw an advice to take the night session because “your classmates will be

working so the average will be lower. So you can score higher and ‘pull up’ your GPA. ”

- There are a few students in class who were visibly struggling. It is chilling to know that some were observing and banking on that.

- We learn to prey on other people’s weaknesses.

- In learning economics, one generally comes across theory of firm collusion and competition. You’d not be aghast that some learn it and take it to their advantage. It is said that we should “talk to and work with only those who are above average so that you form a domination. Guaranteed, you will be above average. ”

Maybe it is not inherently bad to be strategic, because the world is not a utopia. But are we teaching young people to let go of our ideals for mere grades?

- We learn to collude and oppress.

Inquisitiveness.

I feel that the system provides no incentive to ask, and a positive benefit to not ask.

- To an undergraduate student, your inquisitiveness does not matter because it does not help grades. Some schools tell you that we want to “educate a curious next generation of scholars”, yet wants nothing but standardized scores and transcripts for application–not even a statement of purpose.

- We learn that we are our grades.

- There is a famous quote in an undergraduate circle that goes: “It’s fine if you are rubbish. As long as you are above-average rubbish.”

- We learn that success equals grades higher than 1 standard deviation from the mean.

- As your GPA tends toward the average, you learn to ask “strategic” questions. Ask what is covered in the exam, not how we connect this course to another. Ask about specific questions in the problem set, not additional materials that the instructor wanted to cover but could not. Ask about class average to plan for exams, not the concept. I did this for one term. I will be ashamed if I do it again.

- We learn to ask questions without wanting to know.

- Several times you’d do the right thing. You’d try to help others who are weak in the subject and struggling in a class.

You’d be surprised to find that they are more interested taking pictures of your work.

- You’d wonder what exactly is failing. Are you failing the system, or the system is failing the weak?

Leadership.

I always think leadership is about understanding people and things, and taking initiative based on that understanding.

Last term, I heard my housemate Leo talking about an attempt to have a class boycott an assignment. They felt that it was

horribly long and not helpful for the understanding of course material. The class is graded as usual on relative standing:

if no-one in the class did the assignment, they reasoned, no-one’s scores will be hurt.

I was excited for him, because he was doing what he thought was right. However, I am a student of economics.

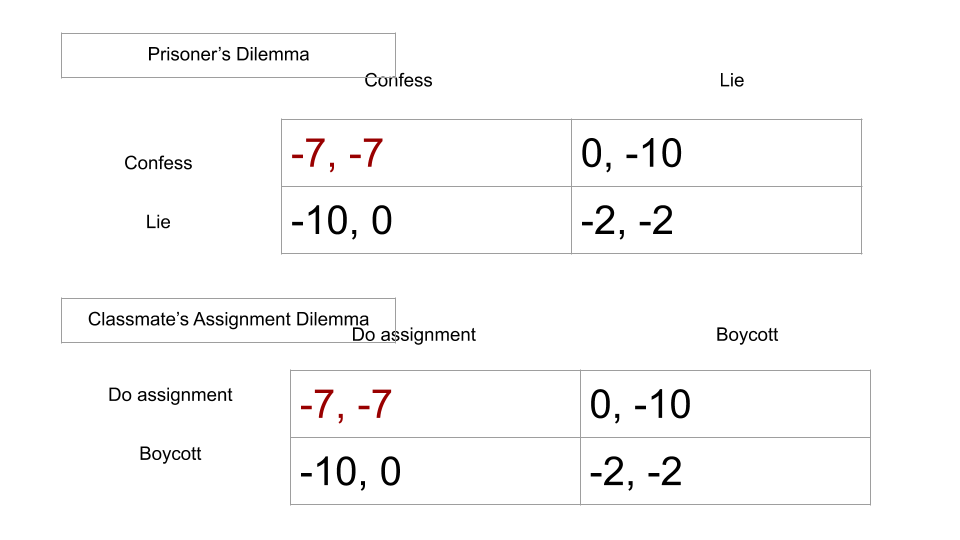

It was a coordination game with the classic prisoner’s dilemma payoffs, and we all know the unique Nash equilibrium of the game:

Prisoner’s Dilemma and Classmate’s Assignment Dilemma

Prisoner’s Dilemma and Classmate’s Assignment Dilemma

Sure enough, the following week I saw them grudgingly working on the assignment together. They were disappointed.

This equilibrium follows from the payoff structure, so that was not surprising. It was disappointing however that the course administration (instructor or department) got upset when told about it. To me, that was the troubling part. If I was the professor, I would assess what is wrong with my assignment than to be upset about a movement against it. Further, if the movement worked and everyone did boycott, I would write recommendations for everyone in the class for their camaraderie and steadfastness, as well as an intelligent solution.

I had the opportunity to present this problem with an economics undergraduate crowd after this happened. It took some time, but we came up with ways like getting everyone together for the weekend and keeping an eye on each other. I thought it was really fun.

If you can understand, organize, lead, and solve a dilemma such as this, the world is your playground. Why don’t we teach or encourage our graduates to learn these skills?

I love my university. Apart from work, the university is practically my home, and the university community is family.

But its over-emphasis on grades is sickening. The system is teaching us to cut corners, be quiet, follow rules when convenient,

do not initiate, care little, and to belittle ourselves and each other.

I never want to learn what it wants me to learn.

** featured image is a photo by Nad X on Unsplash

Written by Natasha. Last edited:2019-06-23 01:53:33