I had a good year with lots of learning.

2018 was definitive in my economics studies. It was arriving at a new institution and finding out that there is no liberal arts economics courses (yes, I should have checked, I should have known.) It was looking past all existing liberal arts foundations and buckling up for the quantitative approach. It was opening up to mathematics, seeing its beauty, and finding out that I can and like to do it. It was further knowing that much more has to be repaired and built.

2018 was about pushing limits, about going past one boundary at a time. It was victory and final rounds at debate tournaments, it was taking part in hackathon and pulling an app out of thin air. It was encountering difficult concepts in class, and actually understanding and using them. It was joining a research team and be able to contribute. It was starting out with manual mining and matching at work last November, and now knowing 5 different ways to do the same thing.

2018 is also a martini with too much vermouth – its bitter end notes still dancing on my tongue. I have taken a beating, and am trying to recover. I’ll pen that sometime, maybe, but in this post, I want to measure my learnings in 2018.

How do you measure learnings?

There are many ways. You can keep track of the number of pens you use to exhaustion, but pens like to disappear. You can record checkpoints e.g. you learn integration by parts today, then by substitution next week; but those are subjective, and in fact quite laborious.

I use the easiest method: I measure time.

By recording only time that I am actually studying – and not being distracted by parliament videos on YouTube – I know that for each hour of studying I learn something. The accrual of study time is a metric for my formal learnings.

This might remind you about the 10,000 hour rule, most commonly attributed to Malcom Gladwell. Actually, deliberate practice theory has been in the research literature for a long time, primarily in the sports, medicine practice and music domains. Gladwell rounded the numbers and made it sound genial.

A lot of assumptions are in order to make hours count a primary metric: the most important one is that hours matter, which is not usually the case. An athlete’s and a musician’s required skills are highly targeted, so it makes sense that practice directly impacts their attainment. The theory maybe less applicable for other job areas varying in terms of predictability: Macnamara and coauthors in 2014 found that deliberate practice explained 26% of the variance in performance for games, 21% for music, 18% for sports, 4% for education, and less than 1% for professions. This instills doubts in whether the time I spend on economics actually counts towards my skills.

In that same vein, I suspect that those who mention Outliers exclusively in reference to the popular rule might not have read the book themselves. Gladwell’s main idea in Outliers is not about proving, or building the rule (it’d be hard to generalize some numbers of hours of work as the make-or-break condition for all skills and professions.) The book is not even about how practice or hard work fundamentally affects one’s fate, but the opposite: effort is just a fraction of the determinant of your success. In Outliers, Gladwell presented an interesting breakdown of the factors, but those merits reach a lot less than the roll-off-the-tongue rule.

Despite all the shortcomings, I measure time because it’s objective and easy. I started collecting my time use data on the 8th of January this year with a software called RescueTime that automatically records what is running on the computer. I also manually enter offline/off-screen time, and collect data on my cellphone activities (until an iPhone ruins everything.)

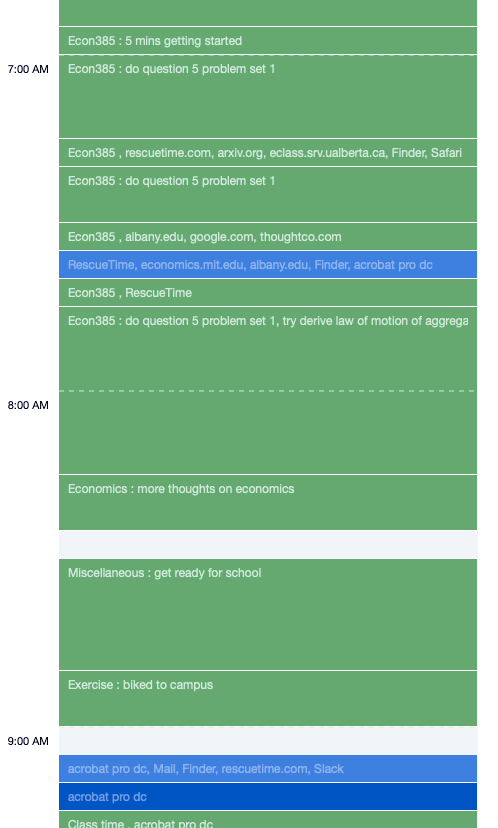

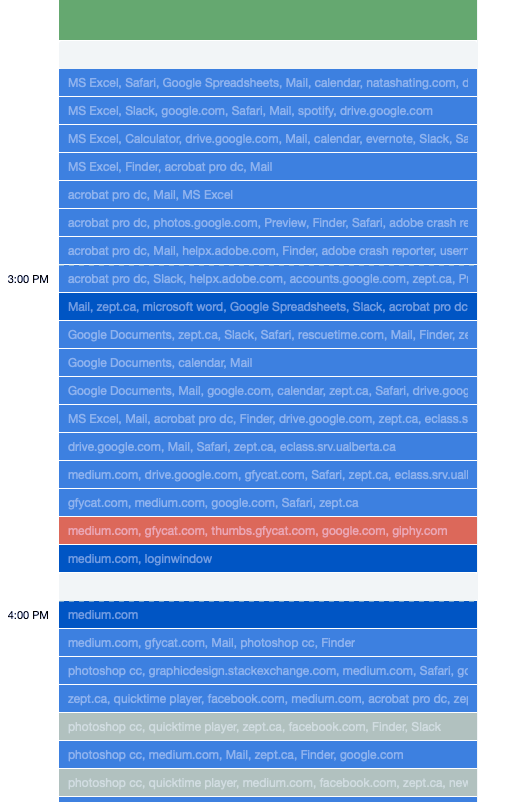

A random day in October looks like this:

more offline/off-screen time

more offline/off-screen time

more computer time

more computer time

They have a built-in analytics dashboard that is quite handy, but you can get or post more data through their API for your own work.

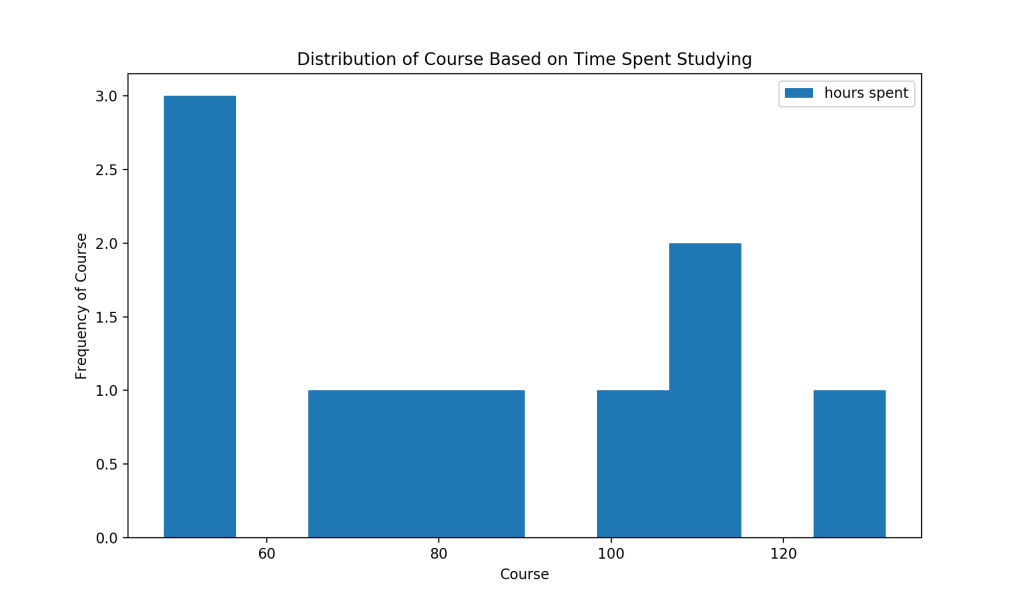

Here are the hours that I spent studying outside of classroom for each of the courses I took in Winter 2018 and Fall 2018:

| Course | Hours |

|---|---|

| Econ303 (offline) | 131.858 |

| Econ200 (offline) | 110.459 |

| Cmpt000 (offline) | 107.823 |

| Math000 (offline) | 100.387 |

| Econ302 (offline) | 85.8228 |

| Econ301 (offline) | 78.7358 |

| Econ300 (offline) | 69.1956 |

| Econ202 (offline) | 56.0883 |

| Engl000 (offline) | 54.3369 |

| Econ201 (offline) | 48.1058 |

These are real data summarized from a year’s collection, but I masked the actual course codes with pseudo ones. Why? Instructors have a tendency to go into nuclear arms race (i.e. making the course harder and harder) if they found out that their courses are not studied as much, thus a sleep-time maximizing student keeps information asymmetry in the marketplace.

Figure 1: distribution of courses based on time spent is quite skewed to the right

Figure 1: distribution of courses based on time spent is quite skewed to the right

Sum: 842.812 —- I spent 842.812 hours this year on studying for my 10 courses.

Mean: 84.2812 —– I spent an average of 84 hours per course per term. This means 84/14 weeks = 6 hours per week on average.

Stdv: 27.935 —– the data is very spread out. Different courses require different commitment.

Adding instruction hours, e-class, and a separate program time, I spent a total of 1234.3925 hours on school this past year => roughly 44 hours per week in a term. If I take a sum of hours of only ECON and MATH courses, the hours count is 985.82. I give this count a special variable name of H_hat. It is an important metrics because I have had but ECON101, ECON102, Calculus I and Stats I before this January. Therefore, I consider my being a student of economics takes off from there.

But how big or small really is 985.52 hours? Well, going back in Malcolm Gladwell (2008), who detailed the success route of The Beatles, Bill Joy and Bill Gates in the 10,000-Hour Rule chapter:

“All told, [The Beatles] performed for 270 nights in just over a year and a half. ” This is in Hamburg, where they “had to play for eight hours, so we (they) really had to find a new way of playing”.

Let’s say 8 hours per night averaging across on-stage and prep hours = 270 x 8 = 2160 hours in 1.5 years. This is around 1,440 in 12 months.

What about Bill Gates?

“In one seven-month period in 1971, Gates and his cohorts ran up 1,575 hours of computer time on the ISI mainframe [at the University of Washington].”

This would mean 2,700 hours in 12 months.

Other studies have varying numbers. A study by Ericsson et al. reports that by 18 years of age, the best violinists and the middle-aged professional violinists had accumulated 7,410 and 7,336 hours in deliberate practice activity, respectively. Campitelli & Gobet (2011) estimated that the minimum requirement to achieve master level in chess is 3,000 hours of deliberate practice.

At 985.82 hours per 12 months, I’d use more than 10 years to reach 10,000. This is very, very modest, not only in comparison with others, but also when compared with the gaggle of other learnings that I’m spending my time on (guess who just spent 5 hours writing a blogpost?)

Thus one of my 2019 resolutions is to raise H_hat to 2,000. Do you think it’s possible?

<———————————————————->

Reference

- Campitelli, G., & Gobet, F. (2011). Deliberate practice: Necessary but not sufficient. Current directions in psychological science, 20(5), 280-285.

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psycholog- ical Review, 100, 363–406. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363

- Gladwell, M. (2008). Outliers: The story of success. Hachette UK.

- Macnamara, B. N., Hambrick, D. Z., & Oswald, F. L. (2014). Deliberate practice and performance in music, games, sports, education, and professions: A meta-analysis. Psychological science, 25(8), 1608-1618.

- Feature Image is a photo by Chris Liverani on Unsplash

Written by Natasha. Last edited:2018-12-28 15:01:29