One time a couple of weeks ago, my friend Greg stopped me at the doorstep to jubilantly tell me “Natasha, we need to give you a surname.”

I was dumbstruck: “What?”

Turned out, my friend did not intend to insult. He merely wanted to give me a nickname in our community chat group. A nickname is called sur nome in French, so he got confused. I was amused, for my father would be ready to fight Greg if he heard the suggestion. I’ve heard that in Western culture last names are significant. Most of us know a Smith (especially if you study economics,) and certain qualities run in the Trumps. In Robert Browning’s epic poem Last Duchess1, the Duke expressed profound pride in his name:

Somehow—I know not how—as if she ranked My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name With anybody’s gift. Who’d stoop to blame This sort of trifling?

Likewise, the Chinese also make a big deal out of last names. This post is about my understanding of the cultural importance of my surname:

The Origins of the Tings

Although there are more than 18,000 Chinese surnames, a surname can be shared by millions of people. For example, the most common surname in China: 张 (also 張; zhang in Han Mandarin pronunciation) registers more than 100 million people, about the population of Canada and United Kingdom combined.

My surname 陈 (also 陳; chen in Han Mandarin pronunciation) comes from a gift by 周武王 King Wu of Zhou (around 1040 BCE) to all descendents of 舜 (one of the five ancient Kings, 4000 BCE). The surname enjoyed an uptake during the Chen Dynasty around CE 557. To differentiate the 陈’s, a specific line within the Chen family tree traces back to the village that one’s ancestors are based in. In my case, I am a 吉洋陈 (JiYang-Chen, or JiYang-Ting), meaning a Ting from JiYang Village. To this day in some cities in Malaysia, you can still see plagues on residential homes that identifies the surname of the household, e.g. a displayed “江夏” (jiang xia) plaque would mean that the family name is 黄 (huang).

My legal surname is not Chen, but Ting, because it’s the way that it’s pronounced in Foo Chow / Ku Tien dialect. China has a one language policy, so my mainland Chinese relatives would be Chen’s but not Ting’s if they had English names. For simplicity, I refer to all Foo Chow-descent 陈’s as Ting’s.

The JiYang-Ting Book

The JiYang-Ting Book

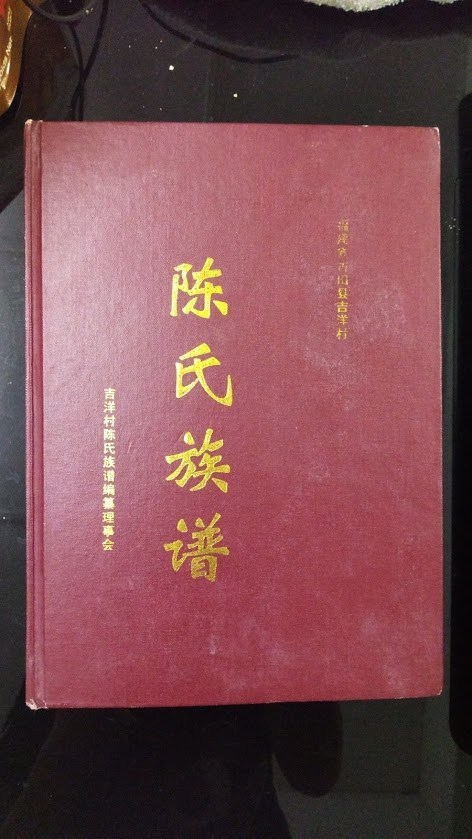

There is a 264-page ancestral archive in my parents’ house that I nickname the Ting Book. The book records the family tree of a man, 陈遂公, who first moved to 福建省古田县吉洋村 (Ji Yang Village in Fujian province, Ku Tien county). He is the 16th generation under , but his moving to Ji Yang Village meant that he became the primogenitor of all JiYang-Ting’s.

The Ting Book, edited in 2011, contains some basic literature about the village, as well as a detailed record of different families that share the same surname: who married whom, who passed away at young age, who moved to other cities, who left China, etc. There are pictures of graveyards of the earlier ancestors, naming conventions in the Ting family (members of each generation supposedly share the same part in theier first names), as well as a simple record of what the younglings’ve been up to.

I am on the 19th generation of this line. If my arithmetic is correct, that means that my JiYang-Ting surname has been in existence for around 1,000 years. Names recorded in the Ting Book lived through the end of Tang Dynasty > Song Dynasty > Yuan Dynasty > Ming Dynasty > Qing Dynasty, to New China, and of course, other overseas jurisdictions such as Malaysia.

Technology may Solve Storage and Data Cleansing Difficulties

Because our family moved away from China, our records stopped at the 16th generation. My father has been especially enthusiastic about feeding our data to the Ting Book since he got his hands on it, but my mother sees little point in my active participation. Females enjoy significantly less recognition in a family history since China became a patriarchal society. It’s clear from the pages that female names aren’t even recorded in earlier generations.

I am less spiteful. To me, the lack of recognition for the gentle sex is attributable not only to the rise of religions, but also accounting convenience. By the looks of it, the editorial team of the Ting Book used little technology in tracing the family history but books, and plain books. Even if they were keen on breaching the Confucius patriarchal conventions, it is hard to account for mobility between families. For each of the woman or man who marry into other families, they’d have to cross-check to make sure that headcount tallies in the end.

With technology, this may change. Right now, the biggest Chinese family heritage data site (http://www.datarural.com/p/jp/Index) still uses a top-down approach, but crowd-sourcing would accelerate data acquisition to phenomenal speeds. Meanwhile, the relational database to graph database evolution may be instrumental in changing the way that data cleansing is done. Cross-checking can become much easier when different nodes in a table is linked to other table. Barring other data privacy concerns, storing information in blockchain may also help with the “identity blackmarket” muddle which thrived under the relentless identify control regime of the central Chinese government.

This by no means implies that I will subject myself to Beijing’s surveillance efforts.

Final thoughts

Tribal pride can be harmful if it is not contained, just like racial pride. Nevertheless, I feel that an ancestral archive does not fuel tribal pride or exclusivity as much as it instills appreciation of the heritage and legacy that humankind can create. We should know our roots without being bound. Roots initiate, but seeds – light, mobile, and compatible with soils other than its own – are what substantiate.

Reference

- Bbc.co.uk. (2016). English Literature Robert Browning: My Last Duchess. [online] Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/gcsebitesize/english_literature/poetrycharactervoice/mylastduchessrev2.shtml [Accessed 29 Jul, 2018].

- 吉洋村陈氏族谱编募理事会. (2011). 福建省古田县吉洋村: 陈氏族谱.

Written by Natasha. Last edited:2018-07-30 13:53:22